Defending Russian Wilderness

In the Nation That Holds One-Eighth the Habitable Globe,

Love of Nature Is Reaching the Peaks of Power

Русская версия (Russian version)

(Originally published in slightly shorter form in EnvironmentYale, Fall 2010,

with photography by Igor Shpilenok <www.shpilenok.ru/>.)

by Fred Strebeigh

Photography by Igor Shpilenok

(Additional photography by Igor Podgorny, by Fred Strebeigh, and courtesy of the Kremlin.)

(Originally published in slightly shorter form in EnvironmentYale, Fall 2010,

with photography by Igor Shpilenok <www.shpilenok.ru/>.)

by Fred Strebeigh

Photography by Igor Shpilenok

(Additional photography by Igor Podgorny, by Fred Strebeigh, and courtesy of the Kremlin.)

Kronotksy Zapovednik, cover photo Igor Shpilenok

President Dmitry Medvedev of Russia, glancing to his right on May 27, 2010, at a high-level government meeting, said, "Let’s listen to the environmentalists." He looked at Igor Chestin, head of the Russia office of WWF (known internationally as the World Wide Fund for Nature), a guest among the high-government officials of the Presidium of the State Council. Not since 2003 had the president of Russia, then Vladimir Putin, convened the presidium to discuss environmental initiatives. That meeting, which produced almost no results, left Russian environmentalists fuming.

Bryansky forest (Shpilenok)

If the government in

Moscow--heir to a history of Soviet environmental mismanagement that helped

desiccate the Aral Sea in Central Asia and melt down the Chernobyl reactor on

the edge of Europe--begins listening to good environmental counsel, the global

environment may reap huge benefits. Russia controls one-eighth the land surface

of the habitable globe and one-fifth of its forested areas, which may store more

carbon than the forestlands of any other country. It is also the world’s largest

exporter of natural gas, second-largest exporter of oil and third-largest

emitter of carbon dioxide after China and the United States.

Russian efforts to manage forestlands to maximize their ability to store carbon, rather

than permit their destruction by fire or by sloppy logging, could significantly

reduce the world’s emissions of carbon dioxide and related impacts on climate

change. Russian efforts to shift toward use of renewable energy such as wind

power, available abundantly in Russia, could drive down its own high emissions.

A reduced dependence on exporting fossil fuels could lessen Russia’s need for

potentially polluting oil and gas exploration in the oceans of its continental

shelf.

Moscow--heir to a history of Soviet environmental mismanagement that helped

desiccate the Aral Sea in Central Asia and melt down the Chernobyl reactor on

the edge of Europe--begins listening to good environmental counsel, the global

environment may reap huge benefits. Russia controls one-eighth the land surface

of the habitable globe and one-fifth of its forested areas, which may store more

carbon than the forestlands of any other country. It is also the world’s largest

exporter of natural gas, second-largest exporter of oil and third-largest

emitter of carbon dioxide after China and the United States.

Russian efforts to manage forestlands to maximize their ability to store carbon, rather

than permit their destruction by fire or by sloppy logging, could significantly

reduce the world’s emissions of carbon dioxide and related impacts on climate

change. Russian efforts to shift toward use of renewable energy such as wind

power, available abundantly in Russia, could drive down its own high emissions.

A reduced dependence on exporting fossil fuels could lessen Russia’s need for

potentially polluting oil and gas exploration in the oceans of its continental

shelf.

Lake Baikal from Barguzinsky Zapovednik, nature reserve founded 1916 (Strebeigh)

A Russian decision to place

environmental controls on the kinds of mineral exploration and oceanic transportation that occur in the increasingly ice-free ocean above its north coast could help protect Arctic regions against environmental damage. And protection of its waterways against pollution could make Russia a source of pure water in an increasingly thirsty world, since Russia possesses 9 percent of the world’s constantly renewing sources of water in its rivers and 26 percent of the world’s stored surface water (most of which is now so pure as to be potable

without filtering) in its lakes.

The idea that Russia’s leaders would listen to Russian environmentalists’ entreaties runs contrary to the experience of many Russians and of people throughout the world. Indeed, most of the world seems unaware of the history and current work of Russian environmentalists on behalf of nature protection and conservation. International awareness about current Russian conservation efforts can, in the words of

Professor Stephen Kellert of the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, seem as dim as a "black hole."

A familiar view appeared this summer in the New York Times, which reported in August 2010 that environmentalists trying to get their government to

listen--with the only forum often being public demonstrations--have for years

"risked arrests and sometimes beatings by the police and masked plainclothes

thugs" and that "such efforts lead to little but holding cells or worse." Adding

clout, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin this summer warned demonstrators who failed

to receive the right kind of advance permit (not always readily offered) to

expect that "you are going to get beaten upside the head with a club." Putin is

usually viewed as the nation’s environmental nemesis, beginning from the start

of his presidency in 2000 when he dissolved the nation’s 200-year-old forest

service and put the nation’s nature reserves under the management of a ministry

whose historic role had been extracting resources by logging and mining rather

than protecting nature. As if to complete the symbolism, then-President Putin

named a builder of highways as the new minister in charge of nature

reserves. A 2008 Newsweek article

said that Russian "officialdom now seems to spend more time cracking down on

ecologists than tackling ecological problems."

environmental controls on the kinds of mineral exploration and oceanic transportation that occur in the increasingly ice-free ocean above its north coast could help protect Arctic regions against environmental damage. And protection of its waterways against pollution could make Russia a source of pure water in an increasingly thirsty world, since Russia possesses 9 percent of the world’s constantly renewing sources of water in its rivers and 26 percent of the world’s stored surface water (most of which is now so pure as to be potable

without filtering) in its lakes.

The idea that Russia’s leaders would listen to Russian environmentalists’ entreaties runs contrary to the experience of many Russians and of people throughout the world. Indeed, most of the world seems unaware of the history and current work of Russian environmentalists on behalf of nature protection and conservation. International awareness about current Russian conservation efforts can, in the words of

Professor Stephen Kellert of the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, seem as dim as a "black hole."

A familiar view appeared this summer in the New York Times, which reported in August 2010 that environmentalists trying to get their government to

listen--with the only forum often being public demonstrations--have for years

"risked arrests and sometimes beatings by the police and masked plainclothes

thugs" and that "such efforts lead to little but holding cells or worse." Adding

clout, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin this summer warned demonstrators who failed

to receive the right kind of advance permit (not always readily offered) to

expect that "you are going to get beaten upside the head with a club." Putin is

usually viewed as the nation’s environmental nemesis, beginning from the start

of his presidency in 2000 when he dissolved the nation’s 200-year-old forest

service and put the nation’s nature reserves under the management of a ministry

whose historic role had been extracting resources by logging and mining rather

than protecting nature. As if to complete the symbolism, then-President Putin

named a builder of highways as the new minister in charge of nature

reserves. A 2008 Newsweek article

said that Russian "officialdom now seems to spend more time cracking down on

ecologists than tackling ecological problems."

"Listen to the Environmentalists"?

Presidium of the State Council (via kremlin.ru)

As Chestin of WWF prepared in May to ask Russia’s president to confront environmental challenges, he had reason to doubt that he would receive support. In opening the Presidium session

(photo at left, via kremlin.ru), President Medvedev remarked that businesses

need to see economic benefits if they attempt environmental modernization.

Following the president, the federal minister of natural resources remarked that

possessing huge territory had permitted the Soviet Union to ignore environmental

issues. The governor of a southern state asked the President to give his

constituents a conference center, ostensibly to start hosting environmental

discussions. And a spokesman for

Russian business argued that environmental improvement hurts national

competitiveness. Those arguments offered snapshots of environmentalists’ fears:

Soviet-legacy environmental errors might seem unfortunate but beyond

remediation; pork-belly projects would get fresh greenwashing; business

interests would continue to prevail over environmental concerns.

"Dear Dmitry Anatolevich," Chestin began, addressing the president with the greeting

that characterized the small meeting. Chestin, looking fierce in his dark suit, a far cry from his preferred

field naturalist’s garb, then went on attack: critiquing Putin’s unproductive 2003

session, which occurred in the same room, for failing to avert what became a

decade of environmental missteps. Medvedev, interrupting as he had not done with

other speakers, tried to block Chestin from dwelling on past problems.

(photo at left, via kremlin.ru), President Medvedev remarked that businesses

need to see economic benefits if they attempt environmental modernization.

Following the president, the federal minister of natural resources remarked that

possessing huge territory had permitted the Soviet Union to ignore environmental

issues. The governor of a southern state asked the President to give his

constituents a conference center, ostensibly to start hosting environmental

discussions. And a spokesman for

Russian business argued that environmental improvement hurts national

competitiveness. Those arguments offered snapshots of environmentalists’ fears:

Soviet-legacy environmental errors might seem unfortunate but beyond

remediation; pork-belly projects would get fresh greenwashing; business

interests would continue to prevail over environmental concerns.

"Dear Dmitry Anatolevich," Chestin began, addressing the president with the greeting

that characterized the small meeting. Chestin, looking fierce in his dark suit, a far cry from his preferred

field naturalist’s garb, then went on attack: critiquing Putin’s unproductive 2003

session, which occurred in the same room, for failing to avert what became a

decade of environmental missteps. Medvedev, interrupting as he had not done with

other speakers, tried to block Chestin from dwelling on past problems.

Young volunteer fights fire in Oksky Zapovednik (Igor Podgorny)

Chestin charged onward. He attacked changes that took effect in 2000 with Putin’s presidency that eliminated environmental assessment of major public works, such as the construction of a ski resort within a national park, and weakened defense of protected natural areas (in which the few rangers who fight fires and arrest poachers now receive salaries as low as $200 a month, just above Russia's official subsistence level of $180). Chestin contended that the government had cut the number of rangers in Russia’s forests by more than 80 percent in a

decade (from 70,000 to 12,000 according to one report), leaving Russia

unprepared when wildfires erupted--as they did a few months after the Presidium meeting, in summer 2010, darkening Moscow with smoke.

Saying almost nothing, the President turned to the other environmentalist invited to the session. Vladimir Zakharov, a professor in the Russian Academy of Sciences and president of an independent organization called the Center for Russian Environmental Policy, argued that "ecology today is economy"--the two are one. President Medvedev, remarking on the environmentalists’ energetic style, said, "There must be someone who beats an alarm." His praise felt faint.

decade (from 70,000 to 12,000 according to one report), leaving Russia

unprepared when wildfires erupted--as they did a few months after the Presidium meeting, in summer 2010, darkening Moscow with smoke.

Saying almost nothing, the President turned to the other environmentalist invited to the session. Vladimir Zakharov, a professor in the Russian Academy of Sciences and president of an independent organization called the Center for Russian Environmental Policy, argued that "ecology today is economy"--the two are one. President Medvedev, remarking on the environmentalists’ energetic style, said, "There must be someone who beats an alarm." His praise felt faint.

A Presidential View of "Ecology and Economics"

Dmitry Medvedev (via kremlin.ru)

Nine days later President

Medvedev went on the Web via video, as he often does when he wishes to speak to

the nation (photo at left via kremlin.ru). Soft light slanted through a forested

park behind him. When he began to make the point that was the title of his

talk--"Ecology and Economics Do Not Contradict Each Other"--the camera cut from

the forest to the previous week’s seminar table, starting with close-ups of

Chestin and Zakharov. At this "ecological moment" in world history, President

Medvedev said, "any normal economy must be environmentally friendly." He noted

that his videos have elicited many environmental pleas from blogging

constituents, and he praised those calling for new environmental laws and more

ecological education.

Would a soft-light video be the only outcome of the president's meeting? No. Shortly afterward Medvedev released a list of 24 environmental orders to the Russian government. They included the following: Devise methods to calculate the economic value of environmental damage. Improve laws to protect Russia’s waters against oil pollution. Improve

financing for Russia’s vast but underfunded protected areas, such as national

parks and zapovedniks (nature reserves). Improve laws to reduce illegal logging

and "corrupt ties" between forestry companies and government officials. Submit

proposals to use anti-pollution fines to fund "eco-efficient and environmental

technologies." Finally, he put in charge the one official whom many Russians

believe may be more powerful than the president--Vladimir Putin, now prime

minister and widely rumored to be awaiting the chance to run for president in

2012, who would be "responsible" for following through on all of the orders,

many of which would address environmental problems that festered during his own

presidency from 2000 to 2008.

Russian environmentalists were floored. WWF-Russia announced that the orders opened "a new chapter in conservation of

our country."

Medvedev went on the Web via video, as he often does when he wishes to speak to

the nation (photo at left via kremlin.ru). Soft light slanted through a forested

park behind him. When he began to make the point that was the title of his

talk--"Ecology and Economics Do Not Contradict Each Other"--the camera cut from

the forest to the previous week’s seminar table, starting with close-ups of

Chestin and Zakharov. At this "ecological moment" in world history, President

Medvedev said, "any normal economy must be environmentally friendly." He noted

that his videos have elicited many environmental pleas from blogging

constituents, and he praised those calling for new environmental laws and more

ecological education.

Would a soft-light video be the only outcome of the president's meeting? No. Shortly afterward Medvedev released a list of 24 environmental orders to the Russian government. They included the following: Devise methods to calculate the economic value of environmental damage. Improve laws to protect Russia’s waters against oil pollution. Improve

financing for Russia’s vast but underfunded protected areas, such as national

parks and zapovedniks (nature reserves). Improve laws to reduce illegal logging

and "corrupt ties" between forestry companies and government officials. Submit

proposals to use anti-pollution fines to fund "eco-efficient and environmental

technologies." Finally, he put in charge the one official whom many Russians

believe may be more powerful than the president--Vladimir Putin, now prime

minister and widely rumored to be awaiting the chance to run for president in

2012, who would be "responsible" for following through on all of the orders,

many of which would address environmental problems that festered during his own

presidency from 2000 to 2008.

Russian environmentalists were floored. WWF-Russia announced that the orders opened "a new chapter in conservation of

our country."

Putin in Franz Josef Land (premier.gov.ru)

Second, said Chestin, environmentalists’ new influence "coincided with a time when Putin started to get interested in large mammals. He loves them." Although I had seen photographs of Putin engaged recently in research expeditions that put him in contact with tigers and polar bears (anesthetized, at right), I balked at Chestin’s use of the word love. It seemed more like political posturing. But Chestin, ferocious as usual, insisted that for Putin the feeling is love: "I’ve seen his personal reactions."

Third, Chestin added, Putin’s presidency left the government bereft of environmental specialists in part because, as Evgeny Shvarts, now director of conservation policy for WWF-Russia, explained in a 2001 article for Russian Conservation News, the Putin-era evisceration of Russia’s federal services responsible for forestry, geology, water purity, nature protection and environmental safety left them with "almost no real responsibility" and led longtime employees to depart lest they later be treated as "scapegoats" for failing to safeguard the natural resources that they had been stripped of the ability to protect. Now when the government needs advice on environmental protection, it often must seek guidance from nongovernmental organizations like the WWF.

Third, Chestin added, Putin’s presidency left the government bereft of environmental specialists in part because, as Evgeny Shvarts, now director of conservation policy for WWF-Russia, explained in a 2001 article for Russian Conservation News, the Putin-era evisceration of Russia’s federal services responsible for forestry, geology, water purity, nature protection and environmental safety left them with "almost no real responsibility" and led longtime employees to depart lest they later be treated as "scapegoats" for failing to safeguard the natural resources that they had been stripped of the ability to protect. Now when the government needs advice on environmental protection, it often must seek guidance from nongovernmental organizations like the WWF.

Origins of a Resurgence

If a resurgence of Russian environmental organizations is occurring, its origins can be traced to decisions in the 1990s by Russian academics and conservationists. Some of the most important involved a 23-year-old Russian environmentalist named Eugene Simonov, who enrolled in 1991 at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies as the Soviet Union was dissolving.

Vsevolod Stepanitskiy (Strebeigh)

Evgeny Shvarts recalls a pivotal meeting in the Moscow apartment of a well-known oceanographer, Vadim Mokievsky. It included an eminent ornithologist, Viktor Zubakin; an assistant adviser to the President of Russia on environmental issues, Svet Zabelin; and the head of Russia’s nature reserves, a much-respected researcher-turned-administrator named Vsevolod Stepanitskiy (photo left). Most of these men had become mentors to Simonov during his undergraduate years while he rose to leadership at Moscow State University in a legendary group called the druzhina (militia) for nature protection. The meeting decided, Shvarts recalls, to make "a direct order to Eugene" to raise money in order to save and "reform and transform the Russian and post-Soviet conservation system." With the Soviet Union in collapse, its zapovedniks--pristine nature reserves that had been protected for most of a century--were at risk of falling victim to hunters and loggers. Simonov does not recall a direct order, but he said the urgency they all felt during that time pushed him to begin a "save-the-zapovedniks program"--a quest to find funds to save Russia’s nature reserves.

At Yale on scholarship, Simonov had no philanthropic contacts. But he had an almost-unknown conservation story to tell: Hidden behind the Iron Curtain--defended for decades by Russian academics and researchers against the depredations of Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and their followers--was the world’s greatest system of scientific nature reserves, begun

in 1916 on the shores of 400-mile-long Lake Baikal.

in 1916 on the shores of 400-mile-long Lake Baikal.

Team leader Tanya Yurchenko, volunteer group Great Baikal Trail, in Barguzinsky (Strebeigh)

Descending down from granite ridges and peaks that begin almost a mile above the Baikal lakeshore, Barguzinsky Zapovednik defends a land of glacial amphitheaters, stone rivers, hanging valleys, upright inselbergs and stepped waterfalls. In its alpine valleys bloom golden rhododendron and purple Siberian tea. Clustered around hot

springs--home to relic species like dwarf dragonflies that belong in the subtropics but survive in Barguzinsky--birches rise 90 feet, white and smooth as marble columns.

Where Barguzinsky reaches the granite cobbles of Baikal, the lake dives a vertical mile to the bottom--the deepest, oldest, most voluminous lake on Earth. Continuing deeper than its own lake floor, the great rift of Baikal descends through another four vertical miles of silt, carried in by tributary streams for some 25 million years. While the Earth’s other lakes have come and gone, Baikal has spread tectonically, enabling the evolution of hundreds of species found nowhere else on earth--all gaining at least partial protection from the presence around Baikal’s shores of three zapovedniks and three national parks.

springs--home to relic species like dwarf dragonflies that belong in the subtropics but survive in Barguzinsky--birches rise 90 feet, white and smooth as marble columns.

Where Barguzinsky reaches the granite cobbles of Baikal, the lake dives a vertical mile to the bottom--the deepest, oldest, most voluminous lake on Earth. Continuing deeper than its own lake floor, the great rift of Baikal descends through another four vertical miles of silt, carried in by tributary streams for some 25 million years. While the Earth’s other lakes have come and gone, Baikal has spread tectonically, enabling the evolution of hundreds of species found nowhere else on earth--all gaining at least partial protection from the presence around Baikal’s shores of three zapovedniks and three national parks.

Caucasian turs (Shpilenok)

In 1919 and 1920, at the urging of Russian scientists and

naturalists, the new Soviet government began to make decisions that would

foster a system of nature reserves. One early decision signed in 1920 by Vladimir

Lenin (who loved hiking and had once imagined becoming a naturalist), created a

zapovednik called Ilmensky to protect a mineral-rich region in the southern

Ural Mountains. In the 1920s and 1930s,

Russian naturalists traversed their continent to establish reserves. In the

Russian Caucasus, Kavkazsky Zapovednik, founded in 1924 and soon intended to

become the main site for reintroducing leopards into European Russia, descends

from its peak at more than 11,000 feet through pastures that hold European

bison and past cliffs that are home to an almost-acrobatic wild goat, the

Caucasian tur.

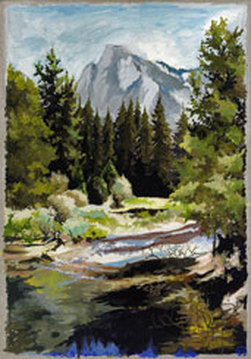

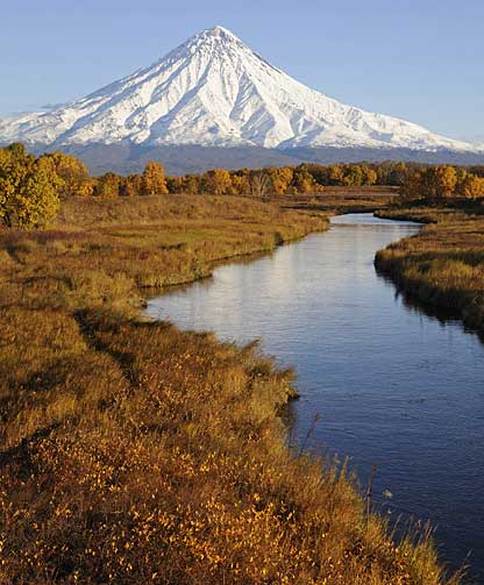

On the Pacific coast of Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, a volcano-studded scimitar slicing into the Pacific, Kronotsky Zapovednik (below, photo by Igor Shpilenok), created in 1935,begins atop snow-topped volcanic cones.

Kronotsky volcano, Kronotsky Zapovednik in autumn (Shpilenok)

Its landscape descends into a valley of spouting geysers, which shoot steam high above riverbanks as colorful as stained

glass. In Kronotsky’s volcano-flanked lakes and rivers, salmon spawn in uncountable millions--as much as one-fifth of the world’s wild salmon spawn in the pristine rivers of Kamchatka. In one abundant Kronotsky-protected lake,

where spawning salmon can number 2 million in a year, brown bear gather in the world’s largest concentration. Government designation of a zapovednik (a word based on "commandment") mandates that its territory remain off-limits to human entry, except for protection by rangers, studies by scientists, and environmental education that can permit bringing limited numbers of visitors.

Simonov got lucky at Yale. In the spring of 1992 he took a course with Stephen Berwick, who was coordinating

major projects in international conservation for the World Bank. After Simonov wrote a paper describing Russia’s zapovedniks, Berwick suggested that it could

become a funding proposal. Once the term ended, Simonov wound up at Berwick’s home, working 72-hour stretches to complete the proposal for submission to the World Bank. The review process would take years.

The first money Simonov brought back to Russia had nothing to do with the World Bank. When Simonov’s Yale studies ended in 1993, he applied to an organization

called Echoing Green for funding to do conservation work in Russia. So did his Yale classmate Margaret Williams, who with his help had spent the summer of 1992 as an environmental educator in Magadansky Zapovednik on Russia’s Sea of Okhotsk at the edge of the Pacific. They

each got grants for $25,000 per year for two years and headed to Moscow. Teamed with Simonov, Williams set about

creating Russian Conservation News, which became an international publishing forum for leading Russian conservationists. Both worked under the umbrella of a newly created organization, Russia’s Biodiversity Conservation Center (BCC), which often seemed to run out of Simonov’s family apartment and, Williams recalls, was a vibrant intellectual salon, filled with leading Russian conservationists and flavored by the smoke from Simonov’s ever-present pipe. Williams, recalls Stepanitskiy, who met her in his role as director of the nature reserve system and then teamed with her at BCC, seemed "like an alive symbol of Russian-American cooperation."

glass. In Kronotsky’s volcano-flanked lakes and rivers, salmon spawn in uncountable millions--as much as one-fifth of the world’s wild salmon spawn in the pristine rivers of Kamchatka. In one abundant Kronotsky-protected lake,

where spawning salmon can number 2 million in a year, brown bear gather in the world’s largest concentration. Government designation of a zapovednik (a word based on "commandment") mandates that its territory remain off-limits to human entry, except for protection by rangers, studies by scientists, and environmental education that can permit bringing limited numbers of visitors.

Simonov got lucky at Yale. In the spring of 1992 he took a course with Stephen Berwick, who was coordinating

major projects in international conservation for the World Bank. After Simonov wrote a paper describing Russia’s zapovedniks, Berwick suggested that it could

become a funding proposal. Once the term ended, Simonov wound up at Berwick’s home, working 72-hour stretches to complete the proposal for submission to the World Bank. The review process would take years.

The first money Simonov brought back to Russia had nothing to do with the World Bank. When Simonov’s Yale studies ended in 1993, he applied to an organization

called Echoing Green for funding to do conservation work in Russia. So did his Yale classmate Margaret Williams, who with his help had spent the summer of 1992 as an environmental educator in Magadansky Zapovednik on Russia’s Sea of Okhotsk at the edge of the Pacific. They

each got grants for $25,000 per year for two years and headed to Moscow. Teamed with Simonov, Williams set about

creating Russian Conservation News, which became an international publishing forum for leading Russian conservationists. Both worked under the umbrella of a newly created organization, Russia’s Biodiversity Conservation Center (BCC), which often seemed to run out of Simonov’s family apartment and, Williams recalls, was a vibrant intellectual salon, filled with leading Russian conservationists and flavored by the smoke from Simonov’s ever-present pipe. Williams, recalls Stepanitskiy, who met her in his role as director of the nature reserve system and then teamed with her at BCC, seemed "like an alive symbol of Russian-American cooperation."

Eugene Simonov, central Asia

The return of Simonov created energy, in part because he quickly spread the wealth from his $25,000 grant. At

the current Moscow offices of the Biodiversity Conservation Center, its walls covered with protected-area maps, I was regaled with stories by Nikolai Sobolev, who in the early 1990s had served in Russia’s Ministry for Environmental Protection and Natural Resources. As Sobolev recalls, Simonov introduced the

idea of adding "ecological corridors" to help connect Russia’s impressive

protected areas into interacting ecological networks. Sobolev also recalls that

the Echoing Green grant got divided by Simonov into separate funds to start

BCC’s ecological networks program; to inaugurate a Center for Russian Nature

Conservation; and to sustain the BCC itself, which by 1994 provided at least

part-time pay to 18 Russian environmental advocates.

Simonov downplays such stories as part of a fanciful legend:

Russia's devoted but embattled conservationists "told Eugene, a lonely

warrior, to go to a far country and get the necessary treasure to support our

nature reserves."

Before any treasure could come from the World Bank, another arrival from America reached Moscow, and she too would play a role in the resurgence of Russian environmentalism. In 1993 Laura

Williams (no relation to Margaret), age 24, with a bachelor’s degree in

environmental policy and superb linguistic skills in Russian, came from

Washington, DC, where her work had been funded by WWF.

Vladimir Krever, a protected-areas specialist who is now WWF-Russia’s

program coordinator for biodiversity, recalls getting a phone call from

Stepanitskiy’s office asking him to come meet "a young girl from the United

States." A vice president of WWF had sent her to inquire about starting a WWF

office in Russia.

the current Moscow offices of the Biodiversity Conservation Center, its walls covered with protected-area maps, I was regaled with stories by Nikolai Sobolev, who in the early 1990s had served in Russia’s Ministry for Environmental Protection and Natural Resources. As Sobolev recalls, Simonov introduced the

idea of adding "ecological corridors" to help connect Russia’s impressive

protected areas into interacting ecological networks. Sobolev also recalls that

the Echoing Green grant got divided by Simonov into separate funds to start

BCC’s ecological networks program; to inaugurate a Center for Russian Nature

Conservation; and to sustain the BCC itself, which by 1994 provided at least

part-time pay to 18 Russian environmental advocates.

Simonov downplays such stories as part of a fanciful legend:

Russia's devoted but embattled conservationists "told Eugene, a lonely

warrior, to go to a far country and get the necessary treasure to support our

nature reserves."

Before any treasure could come from the World Bank, another arrival from America reached Moscow, and she too would play a role in the resurgence of Russian environmentalism. In 1993 Laura

Williams (no relation to Margaret), age 24, with a bachelor’s degree in

environmental policy and superb linguistic skills in Russian, came from

Washington, DC, where her work had been funded by WWF.

Vladimir Krever, a protected-areas specialist who is now WWF-Russia’s

program coordinator for biodiversity, recalls getting a phone call from

Stepanitskiy’s office asking him to come meet "a young girl from the United

States." A vice president of WWF had sent her to inquire about starting a WWF

office in Russia.

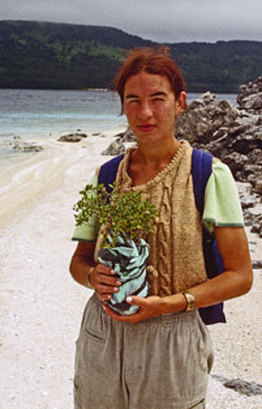

Laura Williams & Igor Shpilenok atop their durable Waz, Bryansk

Soon Krever was "invited to work," he now recalls with an amused chuckle, "under Laura's supervision." WWF rented them a two-bedroom Moscow apartment to serve as an office, and they began inviting applications from nature-reserve directors. One

young director who arrived with an application was the crusading naturalist-photographer Igor Shpilenok, now Laura's husband.

(A disclosure: I taught classes including Laura and Margaret Williams at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, and I knew Eugene Simonov in his student days. Later I collaborated with Igor and Laura, in photo at right, in writing articles on Russia's zapovedniks for Sierra and Smithsonian.) With a few early grants in the range of $100,000 each, funded mainly thanks to WWF-Denmark, Krever and Laura Williams started sending money to support research and education in zapovedniks. But they were fighting a financial crisis.

The Russian government had cut the budget of the nature reserve system from 1990 to 1995--according to inflation-adjusted calculations made by Aleksandr Nikolsky, a professor at th Russian Academy of Sciences who was the last director of the system before the end of the Soviet Union--by about 95%.

In 1996, treasure arrived. The World Bank’s Global Environment Facility (GEF), in response to Simonov's proposal from his Yale days, had decided to support Russian nature conservation with $20 million. "It was like an explosion for us," Krever recalls. "It was an incredible amount of money for Russia in the middle of the 1990s."

young director who arrived with an application was the crusading naturalist-photographer Igor Shpilenok, now Laura's husband.

(A disclosure: I taught classes including Laura and Margaret Williams at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, and I knew Eugene Simonov in his student days. Later I collaborated with Igor and Laura, in photo at right, in writing articles on Russia's zapovedniks for Sierra and Smithsonian.) With a few early grants in the range of $100,000 each, funded mainly thanks to WWF-Denmark, Krever and Laura Williams started sending money to support research and education in zapovedniks. But they were fighting a financial crisis.

The Russian government had cut the budget of the nature reserve system from 1990 to 1995--according to inflation-adjusted calculations made by Aleksandr Nikolsky, a professor at th Russian Academy of Sciences who was the last director of the system before the end of the Soviet Union--by about 95%.

In 1996, treasure arrived. The World Bank’s Global Environment Facility (GEF), in response to Simonov's proposal from his Yale days, had decided to support Russian nature conservation with $20 million. "It was like an explosion for us," Krever recalls. "It was an incredible amount of money for Russia in the middle of the 1990s."

Bison, Bryansk Les Zapovednik (Shpilenok)

Suddenly Simonov and Laura

Williams, while continuing at BCC and WWF-Russia, were lead consultants, working

to apportion millions of dollars allocated by the GEF, and Margaret Williams

became a contributing expert, focusing on nature reserves. Simonov insisted,

against GEF’s preference for a few large allocations, on sending lots of grants

to lots of reserves, supporting some 750 projects that had impact throughout the

continent--allocations like the following: annual $1,600 salaries for

anti-poaching rangers to protect Russian tigers; payments of $12 a ton for 475

tons of winter feed annually for rare European bison (at left, photo by

Shpilenok) at a reserve that breeds endangered species; and an annual $2,400

salary for a scientist to manage a project for restoring rare cranes in flood plains near the Amur River along the Chinese border (photo below, Khingansky Zapovednik). Simonov pushed another policy: get money into the hands of underpaid Russian scholars and naturalists, rather than overpaid outside consultants. "We were managing this $20 million in bags of $1,000 to $20,000," recalls Simonov, and "it drove the World Bank wild." (In those years of a mostly cash economy, they really did use bags.)

Williams, while continuing at BCC and WWF-Russia, were lead consultants, working

to apportion millions of dollars allocated by the GEF, and Margaret Williams

became a contributing expert, focusing on nature reserves. Simonov insisted,

against GEF’s preference for a few large allocations, on sending lots of grants

to lots of reserves, supporting some 750 projects that had impact throughout the

continent--allocations like the following: annual $1,600 salaries for

anti-poaching rangers to protect Russian tigers; payments of $12 a ton for 475

tons of winter feed annually for rare European bison (at left, photo by

Shpilenok) at a reserve that breeds endangered species; and an annual $2,400

salary for a scientist to manage a project for restoring rare cranes in flood plains near the Amur River along the Chinese border (photo below, Khingansky Zapovednik). Simonov pushed another policy: get money into the hands of underpaid Russian scholars and naturalists, rather than overpaid outside consultants. "We were managing this $20 million in bags of $1,000 to $20,000," recalls Simonov, and "it drove the World Bank wild." (In those years of a mostly cash economy, they really did use bags.)

Crane researchers, Khingansky, Amur River (Strebeigh)

The final GEF report praised

Simonov’s project for success that had "no analogs in the scale of public

participation (over 110,000 people) in practical activities on biodiversity

conservation and restoration" and that sent funds to "82 of Russia’s 100 nature

reserves." Berwick said that for Simonov to have convinced GEF to let him--a

young Russian in his mid-20s--allocate millions of dollars to researchers spread

across thousands of square miles of Siberia is "just a total reflection of his

energy and brains."

Spreading funds widely meant

that Simonov had managed a pervasive revitalization of Russia’s conservation

community. Soon many of Russia’s leading conservationists, a large proportion

with doctorates, began to work with Simonov and Margaret Williams at BCC or with

Krever and Laura Williams at WWF, in the process creating durable organizations.

The years took on the aura of a golden age. The acreage of Russian nature

reserves jumped in the 1990s to 83 million from 52 million--approximately

catching up, for the first time since the 1950s when Stalin cut them back in

both size and number, with the acreage of America’s national

parks.

Then came the 2000 election of

Vladimir Putin. His appointment of a former highway builder as the new Minister

of Natural Resources — in charge of mining, logging, and now also pristine

nature reserves— led to an assault on the integrity of reserves, whose directors

were told to make their lands pay. Speaking in front of the directors on October

7, 2001, the new Deputy Minister for Natural Resources in charge of finance

declared that zapovedniks should earn money by cutting forests in their "buffer

zones," which help protect the core areas of some zapovedniks.

In an exchange that Vsevolod Stepanitskiy recalls vividly, the Director

of Altaisky zapovednik, founded in 1932 in spectacular mountains near the

Mongolian border, asked a naive question: "What if a zapovednik does not have a buffer zone?" The deputy minister answered instantly that those zapovedniks must designate some zapovednik forests as "buffers" and then proceed with cutting and selling.

In response, two months later Stepanitskiy quit his job as director and, joined by some members of his team, moved to work with WWF, where he could continue defending Russia's nature reserves. Publicly he announced that he could not stand to watch while the work of his department descended into "useless make-work." When your "work is the work of your life," he continued, "you go to the office with pleasure." But "when going to work is like going behind enemy lines, this is not for me." As one indicator that nature-protection had gone retrograde, in 2005 he noted that the failure to create any zapovedniks from 2001 to 2004 under Putin was matched in duration only by the years from 1951 to 1954.

Simonov’s project for success that had "no analogs in the scale of public

participation (over 110,000 people) in practical activities on biodiversity

conservation and restoration" and that sent funds to "82 of Russia’s 100 nature

reserves." Berwick said that for Simonov to have convinced GEF to let him--a

young Russian in his mid-20s--allocate millions of dollars to researchers spread

across thousands of square miles of Siberia is "just a total reflection of his

energy and brains."

Spreading funds widely meant

that Simonov had managed a pervasive revitalization of Russia’s conservation

community. Soon many of Russia’s leading conservationists, a large proportion

with doctorates, began to work with Simonov and Margaret Williams at BCC or with

Krever and Laura Williams at WWF, in the process creating durable organizations.

The years took on the aura of a golden age. The acreage of Russian nature

reserves jumped in the 1990s to 83 million from 52 million--approximately

catching up, for the first time since the 1950s when Stalin cut them back in

both size and number, with the acreage of America’s national

parks.

Then came the 2000 election of

Vladimir Putin. His appointment of a former highway builder as the new Minister

of Natural Resources — in charge of mining, logging, and now also pristine

nature reserves— led to an assault on the integrity of reserves, whose directors

were told to make their lands pay. Speaking in front of the directors on October

7, 2001, the new Deputy Minister for Natural Resources in charge of finance

declared that zapovedniks should earn money by cutting forests in their "buffer

zones," which help protect the core areas of some zapovedniks.

In an exchange that Vsevolod Stepanitskiy recalls vividly, the Director

of Altaisky zapovednik, founded in 1932 in spectacular mountains near the

Mongolian border, asked a naive question: "What if a zapovednik does not have a buffer zone?" The deputy minister answered instantly that those zapovedniks must designate some zapovednik forests as "buffers" and then proceed with cutting and selling.

In response, two months later Stepanitskiy quit his job as director and, joined by some members of his team, moved to work with WWF, where he could continue defending Russia's nature reserves. Publicly he announced that he could not stand to watch while the work of his department descended into "useless make-work." When your "work is the work of your life," he continued, "you go to the office with pleasure." But "when going to work is like going behind enemy lines, this is not for me." As one indicator that nature-protection had gone retrograde, in 2005 he noted that the failure to create any zapovedniks from 2001 to 2004 under Putin was matched in duration only by the years from 1951 to 1954.

A Spreading Environmentalism

In the past few years, however, changes for the good of the Russian environment began to appear. As I traveled this summer in Russia’s two major cities (Moscow by subway and St. Petersburg by bicycle) to meet with environmentalists, I heard a few key ingredients that may contribute to new Russian environmental leadership.

Build on sound science

Botanist Irina Nevedomskaya, Kurilsky Zapovednik (Strebeigh)

Fulfilling a dream of decades,

a coalition of 200 Russian researchers, led partly by Krever of WWF, in 2008

completed a thorough analysis of gaps in Russia’s protected areas, such as

failures to protect species or ecosystems. It found, for example, that among

Russia's rare and threatened species, protection was adequate for only 51

percent of mammals, 41 percent of birds, and 36 percent of reptiles. Their gap

analysis calls for increasing Russia’s total protected areas to 500 million

acres, 10 percent of the country--a number reached, Krever says, based on

scientific justifications such as adequacy of protection for Russian wildlife.

Stepanitskiy, rehired by the government to run the office of zapodveniks and parks, is now drawing on this analysis to make a case for greatly expanding Russian protected areas. Although the numbers were not yet official when we spoke in July 2010, Stepanitskiy told

me that a hoped-for target would be 11 new zapovedniks and 20 new national parks

by 2020. He declined to predict a total area, but another source told me that Stepanitskiy’s team hoped to increase zapovedniks by 5 million acres, to more than 88 million, and to nearly double Russia’s national park lands to 38 million acres.

Federal funding must increase, said Stepanitskiy, but he has managed for years on slim budgets: $128 million in 2011 for Russia’s 102 zapovedniks and 42 national parks, covering 107 million acres. (His 2011 budget would run America’s National Park System, at 84 million

acres, for 16 days.) Winning protection for more than 20 million more acres

within a decade may prove tough in a difficult economy.

But, says Stepanitskiy--renowned as a defender of nature who has quit his

job three times in order to upbraid government from outside, and who three times

has been rehired--"I will be doing my best."

a coalition of 200 Russian researchers, led partly by Krever of WWF, in 2008

completed a thorough analysis of gaps in Russia’s protected areas, such as

failures to protect species or ecosystems. It found, for example, that among

Russia's rare and threatened species, protection was adequate for only 51

percent of mammals, 41 percent of birds, and 36 percent of reptiles. Their gap

analysis calls for increasing Russia’s total protected areas to 500 million

acres, 10 percent of the country--a number reached, Krever says, based on

scientific justifications such as adequacy of protection for Russian wildlife.

Stepanitskiy, rehired by the government to run the office of zapodveniks and parks, is now drawing on this analysis to make a case for greatly expanding Russian protected areas. Although the numbers were not yet official when we spoke in July 2010, Stepanitskiy told

me that a hoped-for target would be 11 new zapovedniks and 20 new national parks

by 2020. He declined to predict a total area, but another source told me that Stepanitskiy’s team hoped to increase zapovedniks by 5 million acres, to more than 88 million, and to nearly double Russia’s national park lands to 38 million acres.

Federal funding must increase, said Stepanitskiy, but he has managed for years on slim budgets: $128 million in 2011 for Russia’s 102 zapovedniks and 42 national parks, covering 107 million acres. (His 2011 budget would run America’s National Park System, at 84 million

acres, for 16 days.) Winning protection for more than 20 million more acres

within a decade may prove tough in a difficult economy.

But, says Stepanitskiy--renowned as a defender of nature who has quit his

job three times in order to upbraid government from outside, and who three times

has been rehired--"I will be doing my best."

Build support through education

Natalia Danilina

Educational training for zapovednik staff is now coordinated in Moscow by the Environmental

Education Center "Zapovedniks," under the direction of Natalia Danilina (photo

below right), a former vice president of the Commission on National Parks and

Protected Areas of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Among the messages her educators promote, says Danilina, is that Russia’s transition to democracy makes it

"impossible to conserve nature only with a gun"--that armed rangers, who once

stopped citizens from intruding in zapovedniks, need to become also informed

educators. (One of the best eco-walks I've taken in my life was led, a few summers ago along

the Baikal lakeshore in Barguzinsky Zapovednik, by a 20-year-old ranger, Ilya Golubtsov (photo left), who grew up in the reserve and could identify every hint of wildlife, from

distant birdcalls to trailside bear markings.

Education Center "Zapovedniks," under the direction of Natalia Danilina (photo

below right), a former vice president of the Commission on National Parks and

Protected Areas of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Among the messages her educators promote, says Danilina, is that Russia’s transition to democracy makes it

"impossible to conserve nature only with a gun"--that armed rangers, who once

stopped citizens from intruding in zapovedniks, need to become also informed

educators. (One of the best eco-walks I've taken in my life was led, a few summers ago along

the Baikal lakeshore in Barguzinsky Zapovednik, by a 20-year-old ranger, Ilya Golubtsov (photo left), who grew up in the reserve and could identify every hint of wildlife, from

distant birdcalls to trailside bear markings.

Ilya Golubtsov roasting fish at campfire, Lake Baikal

He also made clear that no visitor could depart from our one thin

trail--we were not in a park but in a zapovednik, which mandated that our

footsteps there were limited and precious.) In the new Russia, Danilina wants "our

electorate" to understand the values that lie behind strict protection of

significant landscapes in the natural world.

trail--we were not in a park but in a zapovednik, which mandated that our

footsteps there were limited and precious.) In the new Russia, Danilina wants "our

electorate" to understand the values that lie behind strict protection of

significant landscapes in the natural world.

Go to the streets

Baikal banner at White House, April 27, 2010 (photos Igor Podgorny)

In April 2010, under a bright

blue sky, three young Russians wearing blaze-orange jumpsuits and climbing gear

strolled from a Moscow street toward a 20-foot-high fence that protects the

grand entrance of the Russian White House, headquarters for Prime Minister Putin

(photo right). Each climber,

"Greenpeace" emblazoned on his back, zipped upward to a position astride the

fence. They unspooled a

100-foot-wide, lemon-yellow banner, its jet-black letters as high as six feet,

asking: "Who's enemy of Baikal No. 1 of 13 January 2010?"

The obvious answer would be Putin. His decree (marked "No. 1") on January

13 had opened Lake Baikal to renewed pollution by an antiquated paper-making

factory that dumps chlorine, dioxins and other pollutants into the otherwise

pure lake. Armed White House guards raced towards the fence. They made no arrests. The Greenpeace climbers walked away.

In Moscow, I asked Andrey Petrov, head of his nation’s Greenpeace program to support World Heritage sites (Lake Baikal is one) if he thought the guards might have fired on his climbers. "I hope no," he said, mumbling slightly. But such bold actions for Baikal, he continued, would remain "part of our chain of actions" and "we will not stop before the point at which we solve the problem."

blue sky, three young Russians wearing blaze-orange jumpsuits and climbing gear

strolled from a Moscow street toward a 20-foot-high fence that protects the

grand entrance of the Russian White House, headquarters for Prime Minister Putin

(photo right). Each climber,

"Greenpeace" emblazoned on his back, zipped upward to a position astride the

fence. They unspooled a

100-foot-wide, lemon-yellow banner, its jet-black letters as high as six feet,

asking: "Who's enemy of Baikal No. 1 of 13 January 2010?"

The obvious answer would be Putin. His decree (marked "No. 1") on January

13 had opened Lake Baikal to renewed pollution by an antiquated paper-making

factory that dumps chlorine, dioxins and other pollutants into the otherwise

pure lake. Armed White House guards raced towards the fence. They made no arrests. The Greenpeace climbers walked away.

In Moscow, I asked Andrey Petrov, head of his nation’s Greenpeace program to support World Heritage sites (Lake Baikal is one) if he thought the guards might have fired on his climbers. "I hope no," he said, mumbling slightly. But such bold actions for Baikal, he continued, would remain "part of our chain of actions" and "we will not stop before the point at which we solve the problem."

Go to the world

Andrey Petrov (Strebeigh)

As we spoke in July 2010,

Petrov (right) was preparing to fly to Brasilia for the annual meeting of the

UN’s World Heritage Committee. He would take a letter by members of the Russian Academy of Sciences that accused Putin of violating Russia’s agreement, made when it nominated Lake Baikal for World Heritage status, to stop the mill from polluting the lake's crystal-clear

waters. The Academicians condemned the mill for generating atmospheric emissions and 86% of all water pollution entering Baikal.

Two weeks later, the World Heritage Committee announced its Baikal decision. Under evident pressure in Brasilia, the Russian government committed itself to end the plant’s pollution of Baikal within 30 months. Based on this promise, the World Heritage committee refrained from issuing sanctions. Russian environmentalists remain wary of breakable promises, but they showed they can work successfully with a mix of local and international forces to press their government on environmental issues.

Petrov (right) was preparing to fly to Brasilia for the annual meeting of the

UN’s World Heritage Committee. He would take a letter by members of the Russian Academy of Sciences that accused Putin of violating Russia’s agreement, made when it nominated Lake Baikal for World Heritage status, to stop the mill from polluting the lake's crystal-clear

waters. The Academicians condemned the mill for generating atmospheric emissions and 86% of all water pollution entering Baikal.

Two weeks later, the World Heritage Committee announced its Baikal decision. Under evident pressure in Brasilia, the Russian government committed itself to end the plant’s pollution of Baikal within 30 months. Based on this promise, the World Heritage committee refrained from issuing sanctions. Russian environmentalists remain wary of breakable promises, but they showed they can work successfully with a mix of local and international forces to press their government on environmental issues.

Collaborate across oceans

Kamchatka salmon (Shpilenok)

In late summer 2010, Tom

Brokaw (NBC News) and James Wolfensohn (former president, World Bank) joined the

head of the Wild Salmon Center, Guido Rahr -- a sixth-generation Oregonian whose

family witnessed the disappearance of wild salmon from their home rivers in

Oregon--on one of the world's great salmon rivers, flowing beneath the volcanoes

of the Kamchatka peninsula.

They spent days doing catch-and-release fly fishing and evenings discussing ways to help defend

Kamchatka's wildlife for all time. Rahr first fished Kamchatka rivers in 1993 in the company of a legendary Russian fisheries biologist, Mikhail Skopets, thanks to guidance from his Yale

classmate, Margaret Williams. Fishing then with Skopets, who works in Russia's Institute of Biological Problems of the North and whom Rahr calls "the Indiana Jones of salmon in the Russian Far East," Rahr learned that perhaps as much as one fifth of the world's wild salmon spawn in the pristine rivers of Kamchatka.

Brokaw (NBC News) and James Wolfensohn (former president, World Bank) joined the

head of the Wild Salmon Center, Guido Rahr -- a sixth-generation Oregonian whose

family witnessed the disappearance of wild salmon from their home rivers in

Oregon--on one of the world's great salmon rivers, flowing beneath the volcanoes

of the Kamchatka peninsula.

They spent days doing catch-and-release fly fishing and evenings discussing ways to help defend

Kamchatka's wildlife for all time. Rahr first fished Kamchatka rivers in 1993 in the company of a legendary Russian fisheries biologist, Mikhail Skopets, thanks to guidance from his Yale

classmate, Margaret Williams. Fishing then with Skopets, who works in Russia's Institute of Biological Problems of the North and whom Rahr calls "the Indiana Jones of salmon in the Russian Far East," Rahr learned that perhaps as much as one fifth of the world's wild salmon spawn in the pristine rivers of Kamchatka.

Kamchatka brown bears (Shpilenok)

When Rahr presents his vision

for Wild Salmon Center's current work in Russia, as he did in a half-hour

session that helped encourage Wolfensohn to become an ally, the key document is

a map that shows a Russo-American littoral arching almost unbroken across the

North Pacific--a necklace with pendant peninsulas and deepcut bays that twists

thousands of miles with only a single gap, 55 miles at the Bering Strait, where

Asia until some 15,000 years ago bridged to America.

That map shows most of the world's great preserved salmon rivers, many of

them mapped for emphasis in ruby red. A few, like small jewels, appear as

vestigial decoration along the coast of Oregon, Washington, and British

Columbia; an abundance of ruby shows above Bristol Bay in Alaska; and as the

necklace reaches Russia, rubies large and small array themselves around both

coasts of wasp-waisted Kamchatka and continue on to the flanks of Sakhalin

Island and then mainland Russia before the ruby-colored gleam stops abruptly,

north of China. That map, showing in ruby red the salmon riches that the Americas have mostly lost (except in Alaska) and Russia mostly retained, combines well with Rahr's main argument about salmon rivers: Save them

before you lose them. Restoration costs more, and works worse, than protection of what the world has not lost.

for Wild Salmon Center's current work in Russia, as he did in a half-hour

session that helped encourage Wolfensohn to become an ally, the key document is

a map that shows a Russo-American littoral arching almost unbroken across the

North Pacific--a necklace with pendant peninsulas and deepcut bays that twists

thousands of miles with only a single gap, 55 miles at the Bering Strait, where

Asia until some 15,000 years ago bridged to America.

That map shows most of the world's great preserved salmon rivers, many of

them mapped for emphasis in ruby red. A few, like small jewels, appear as

vestigial decoration along the coast of Oregon, Washington, and British

Columbia; an abundance of ruby shows above Bristol Bay in Alaska; and as the

necklace reaches Russia, rubies large and small array themselves around both

coasts of wasp-waisted Kamchatka and continue on to the flanks of Sakhalin

Island and then mainland Russia before the ruby-colored gleam stops abruptly,

north of China. That map, showing in ruby red the salmon riches that the Americas have mostly lost (except in Alaska) and Russia mostly retained, combines well with Rahr's main argument about salmon rivers: Save them

before you lose them. Restoration costs more, and works worse, than protection of what the world has not lost.

Kol River research station (WSC)

Working with Russian

scientists as Rahr has since 1993, and now collaborating with Moscow State

University and the governor of Kamchatka among others, the Wild Salmon Center in

2006 helped create what it calls "world's first protected area dedicated to wild

salmon conservation," an area of 544,000 acres (more than two-thirds the size of

Rhode Island) that protects the entire watershed of a crystalline river called

the Kol. An allocation of about

$200,000, part of a collaboration linking WSC with the Global Environment

Facility (which is contributing $3 million to a shared project supporting

conservation and sustainable use of salmon in Kamchatka), went to creating a

riverside research station (photo at left, via Wild Salmon Center) where

biologists from Moscow and Kamchatka now team with Americans to develop lessons

for salmon conservation.

scientists as Rahr has since 1993, and now collaborating with Moscow State

University and the governor of Kamchatka among others, the Wild Salmon Center in

2006 helped create what it calls "world's first protected area dedicated to wild

salmon conservation," an area of 544,000 acres (more than two-thirds the size of

Rhode Island) that protects the entire watershed of a crystalline river called

the Kol. An allocation of about

$200,000, part of a collaboration linking WSC with the Global Environment

Facility (which is contributing $3 million to a shared project supporting

conservation and sustainable use of salmon in Kamchatka), went to creating a

riverside research station (photo at left, via Wild Salmon Center) where

biologists from Moscow and Kamchatka now team with Americans to develop lessons

for salmon conservation.

Kuril Lake, South Kamchatka Sanctuary (Shpilenok)

Out ahead, Wild Salmon Center hopes Kamchatka will offer forms of protection, including

ones that would support controlled tourism and a mix of

commercial fishing and sport fishing, to a total of nine

Kamchatkan river systems--protecting 6 million acres of

salmon-rich watersheds and the high numbers

of bears and eagles that thrive there thanks to salmon. These

efforts in thinly populated Kamchatka--larger than California

but with only 110,000 inhabitants living beyond the streets

of its one small city--align with a view expressed in

2009 by Olga Krever, former head of a

department for protected areas in Russia's Ministry of Natural

Resources who is now working partly with Wild Salmon

Center: "Only in Russia do we still have

the chance to preserve large areas and intact wilderness."

ones that would support controlled tourism and a mix of

commercial fishing and sport fishing, to a total of nine

Kamchatkan river systems--protecting 6 million acres of

salmon-rich watersheds and the high numbers

of bears and eagles that thrive there thanks to salmon. These

efforts in thinly populated Kamchatka--larger than California

but with only 110,000 inhabitants living beyond the streets

of its one small city--align with a view expressed in

2009 by Olga Krever, former head of a

department for protected areas in Russia's Ministry of Natural

Resources who is now working partly with Wild Salmon

Center: "Only in Russia do we still have

the chance to preserve large areas and intact wilderness."

Involve national leadersIn late August 2010, Prime Minister Putin joined the director of Kronotsky Zapovednik in a small speedboat for a close look at Kamchatka’s abundant bears and salmon. The excursion gave the new director, Tikhon Shpilenok (son of Igor),

an opportunity to describe poaching horrors. After hearing about the slaughter of hundreds of bears in a recent year, sometimes just for their paws, and salmon by the thousands, slit open for their roe and left to rot, Putin expressed outrage. He said Kamchatka could become instead the world’s premier place for eco-tourism. Asked why he spends so much time among wild animals, Putin replied, "Because I like it. I love nature." In November 2010 (as this article was being printed), Putin hosted a summit of world leaders, including the premier of China, to focus on saving wild tigers from extinction. |

Putin, radio-collared tiger, Ussuri Zapovednik

Putin announced proudly that "Russia is

the only country in the world whose tiger population has significantly grown

since the mid twentieth century"--from about 30 tigers to a current population

near 500, thanks significantly to work begun by researchers in Russian

zapovedniks. By collaborating in

an unprecedented effort by government leaders (joined by the current head of the

World Bank) to protect these "splendid big cats" and their wide-ranging

habitats, Putin announced, "we are saying that human civilization can only

develop sustainably if we take a responsible attitude to nature, our common

home."

the only country in the world whose tiger population has significantly grown

since the mid twentieth century"--from about 30 tigers to a current population

near 500, thanks significantly to work begun by researchers in Russian

zapovedniks. By collaborating in

an unprecedented effort by government leaders (joined by the current head of the

World Bank) to protect these "splendid big cats" and their wide-ranging

habitats, Putin announced, "we are saying that human civilization can only

develop sustainably if we take a responsible attitude to nature, our common

home."

Vote for an environmental president?

What to make of a Russian Prime Minister who, though he slashed Russia’s environmental protections when

first elected President in 2000, now insists that he "loves nature"? And what to make of a Russian President who orders his government to do what Russia’s environmental leaders have asked and who has called Russia's wildfires of summer 2010 "a wake-up call" telling the world's leaders that they must "take a more energetic approach to countering the global changes to the climate"? Why would Russia's leaders begin listening to and sounding like environmentalists?

first elected President in 2000, now insists that he "loves nature"? And what to make of a Russian President who orders his government to do what Russia’s environmental leaders have asked and who has called Russia's wildfires of summer 2010 "a wake-up call" telling the world's leaders that they must "take a more energetic approach to countering the global changes to the climate"? Why would Russia's leaders begin listening to and sounding like environmentalists?

Banner on Moscow River, May 20, 2010 (photo Podgorny)

The most interesting analysis I heard in summer 2010 came from Alexey Kiselev, a specialist on pollution issues, whom I met at the offices of Greenpeace in St. Petersburg. He had just finished a month of testing for dangerous chemicals in three iconic rivers--the Volga, the Neva, and the Moscow.

Traveling aboard the Greenpeace ship Beluga II, he had deplored some ugly

pollution and admired another vast lemon-colored banner, which a Greenpeace

action team had draped in May over a bridge across the Moscow River near the

Kremlin. The banner proclaimed, in Russian and English: "Putin! Ban Toxic Discharges To Our Rivers." Again wearing bright orange, the young Greenpeace team slipped off unarrested, this time cruising the Moscow River in inflatable dinghies.

Reminding me that President Medvedev’s recent orders for environmental improvements listed Putin as "responsible," Kiselev suggested Medvedev was firing a first pre-election salvo

at Putin: You broke it. Now accept responsibility for trying to fix it.

At a time when many Russians were wondering if they might in 2012 see the first hotly contested presidential

election in their history, pitting Putin against Medvedev, Kiselev suggested a direction I had not heard. Perhaps

each of Russia's current leaders, sensing a spreading environmentalism among the people, was preparing to campaign that he would be the president best able to defend Russia's splendid but recently besieged environment. In any event, an ecological vision of "our common home" has apparently found new spokesmen atop the government that holds one-eighth of our populated globe. Russia’s leaders may sense--in the thousands of citizens who march for parks or rally for Baikal or flee from raging fires--the beginnings of a broad environmental awakening.

Traveling aboard the Greenpeace ship Beluga II, he had deplored some ugly

pollution and admired another vast lemon-colored banner, which a Greenpeace

action team had draped in May over a bridge across the Moscow River near the

Kremlin. The banner proclaimed, in Russian and English: "Putin! Ban Toxic Discharges To Our Rivers." Again wearing bright orange, the young Greenpeace team slipped off unarrested, this time cruising the Moscow River in inflatable dinghies.

Reminding me that President Medvedev’s recent orders for environmental improvements listed Putin as "responsible," Kiselev suggested Medvedev was firing a first pre-election salvo

at Putin: You broke it. Now accept responsibility for trying to fix it.

At a time when many Russians were wondering if they might in 2012 see the first hotly contested presidential

election in their history, pitting Putin against Medvedev, Kiselev suggested a direction I had not heard. Perhaps

each of Russia's current leaders, sensing a spreading environmentalism among the people, was preparing to campaign that he would be the president best able to defend Russia's splendid but recently besieged environment. In any event, an ecological vision of "our common home" has apparently found new spokesmen atop the government that holds one-eighth of our populated globe. Russia’s leaders may sense--in the thousands of citizens who march for parks or rally for Baikal or flee from raging fires--the beginnings of a broad environmental awakening.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fred Strebeigh, senior lecturer in the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and the Yale

Department of English, has written for Atlantic Monthly, Audubon, New Republic,

Russian Life, Sierra, Smithsonian, the New York Times Magazine, and the books

division of the National Geographic Society. He is indebted for the chance once

again to share pages with the photography of Igor Shpilenok, whose work can be

seen collected at <www.shpilenok.ru/>

and growing daily at <http://shpilenok.livejournal.com/> . Igor Shpilenok's photography is becoming

as important to Russia's zapovedniks (nature reserves), Fred believes, as the photography of Ansel Adams was to Yosemite

National Park and the grandeur of western North America.

Fred also thanks Igor Podgorny, a young Russian photographer and field geologist, whose photographs

here give a brief hint of his important work emerging continually at <http://igorpodgorny.livejournal.com/> .

(This article first appeared in slightly shorter form in EnvironmentYale, Fall 2010, pages 2-9 and 28,

available at <http://environment.yale.edu/magazine/fall2010/defending-russian-wilderness/>. This longer version restores some cuts

made to fit available pages in a paper publication and reflects some updating thanks to commentary from Russian experts on the zapovednik system. I am indebted to Dave DeFusco, editor of EnvironmentYale, for supporting this article and for using Igor Shpilenok's photos to create a beautiful on-paper version of this article. -- Fred Strebeigh, February 2011)

Русская версия (Russian version)

Russian nature, related articles

[Click here to return to top of page]

Fred Strebeigh, senior lecturer in the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and the Yale

Department of English, has written for Atlantic Monthly, Audubon, New Republic,

Russian Life, Sierra, Smithsonian, the New York Times Magazine, and the books

division of the National Geographic Society. He is indebted for the chance once

again to share pages with the photography of Igor Shpilenok, whose work can be

seen collected at <www.shpilenok.ru/>

and growing daily at <http://shpilenok.livejournal.com/> . Igor Shpilenok's photography is becoming

as important to Russia's zapovedniks (nature reserves), Fred believes, as the photography of Ansel Adams was to Yosemite

National Park and the grandeur of western North America.

Fred also thanks Igor Podgorny, a young Russian photographer and field geologist, whose photographs

here give a brief hint of his important work emerging continually at <http://igorpodgorny.livejournal.com/> .

(This article first appeared in slightly shorter form in EnvironmentYale, Fall 2010, pages 2-9 and 28,

available at <http://environment.yale.edu/magazine/fall2010/defending-russian-wilderness/>. This longer version restores some cuts

made to fit available pages in a paper publication and reflects some updating thanks to commentary from Russian experts on the zapovednik system. I am indebted to Dave DeFusco, editor of EnvironmentYale, for supporting this article and for using Igor Shpilenok's photos to create a beautiful on-paper version of this article. -- Fred Strebeigh, February 2011)

Русская версия (Russian version)

Russian nature, related articles

[Click here to return to top of page]